A breakthrough invention in wearable technology has the potential to change how we interact with the clothes we wear every day.

A new study by researchers at the University of Minnesota Design of Active Materials and Structures Lab (DAMSL) and Wearable Technology Lab (WTL) details the development of a temperature-responsive textile that can create self-fitting garments powered only by body heat. The study was led by graduate students Kevin Eschen (Mechanical Engineering) and Rachael Granberry (Apparel Studies) and professors Julianna Abel (Mechanical Engineering) and Brad Holschuh (Apparel Design) and recently published in Advanced Materials Technologies.

“This is an important step forward in the creation of robotic textiles for on-body applications,” said Holschuh. “It’s particularly exciting because it solves two significant problems simultaneously: how to create usable actuation, or movement, without requiring significant power or heat, and how to conform a textile or garment to regions of the body that are irregularly shaped.”

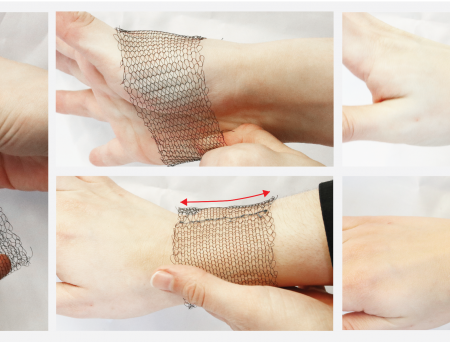

The textiles resemble typical knits, except they use a unique category of active materials — shape memory alloys (SMAs) — which change shape when heated.

In partnership with NASA, U of M researchers studied the unique dimensions of a human leg. They subsequently designed, manufactured, and tested an SMA-based knitted garment that can precisely conform to a leg’s topography.

“This technology required advancements on multiple scales,” said Abel. “At the material scale, we tuned it to respond to body temperature without added power. Structurally, we manufactured it to perfectly adapt to the human body's complex shapes. At the system level, we created an operation that maps the mechanical performance of textiles to human anatomy. Each advancement is important and, together, they create a functionality that didn’t previously exist.”

These knits can be used in custom garments that easily transform from loose to tight and even bend to conform to irregularly shaped regions of the body (e.g., the back of the knee). Examples of future applications include creating compression garments that are initially loose-fitting and easy to put on but can subsequently shrink to squeeze the wearer.

“This creates an exciting new opportunity to create garments that can physically transform over time, which has significant implications for medical, aerospace, and commercial applications,” explained Holschuh.

The next steps will be to integrate the textiles into full-sized garments, which could solve problems where fit and conformance to the body are crucial, such as medical-grade compression stockings.

This research was funded through a NASA Space Technology Research Fellowship and MnDRIVE.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 1 in 68 children in the United States has autism spectrum disorder. This spring, Professor Abimbola Asojo and Instructor Tina Patel's sophomore interior design studio worked with local design firm Perkins + Will and autism service provider Fraser to learn more about designing for those on the autism spectrum.

When Simon Ozbek (MS '20, Human Factors & Ergonomics) started his academic career he never could have imagined that it would take him all the way to NASA. Determined to unite his passions for psychology and creativity, he discovered the College of Design’s Human Factors & Ergonomics graduate program. Now a human factors engineer at NASA, Ozbek describes his journey into the field in the following interview.

The fields of medical device and apparel design may not seem to have a lot in common, but alumni from the College of Design are changing that.