In 1972, Clinton Navarro Hewitt was hired at the University of Minnesota and quickly promoted to Associate VP of Planning. For the next 37 years, Hewitt would shape the U of M’s campuses across the state through dozens of landmark building projects—including Scholar’s Walk, David M. Lilly Plaza, and the Weisman Art Museum—and impact the lives of countless students and colleagues. To celebrate his career of building community and expanding the field of landscape architecture, the Department of Landscape Architecture has worked with the UMN Archives to create the Clinton N. Hewitt archive.

A before-and-after processing image of floppy discs in the Clint Hewitt archive. Credit: UMN Archives.

It wasn’t just what Hewitt did, but how he did it.

Hewitt’s influence continues to permeate the Department of Landscape Architecture, where he taught after leaving his campus planning position. Although he retired in 2009, Hewitt visits campus and Rapson Hall on occasion and his legacy still touches the lives of students and former colleagues.

The Clinton N. Hewitt Fellowship and Campus Planning & Design Study Fund, both established by life-long friend and contractor Mort Mortenson of Mortenson Construction, continue to provide graduate and undergraduate students as well as faculty with support in their teaching and research in the fields of landscape architecture and campus planning.

"The [fellowship] allowed me to explore landscape architecture to continue Clint’s legacy. With the award, I researched campus planning and security and post 9/11 security measures. This work has given me a unique and diverse understanding of the field that I will carry with me into my professional work," commented alumnus Jordan Hedlund (MLA, ’21).

Inextricable from Hewitt’s professional accomplishments are his calm disposition and magnetic personality. “What makes Clint’s presence so special is that he does everything with passion and joy,” reflected Amanda Smoot, landscape architecture department administrator. “Every conversation we’ve had—whether about campus planning or being a Black leader in the 70’s, housing and homeownership—any conversation we have is passionate and joyful, even if it is simply about buying pens at the bookstore.”

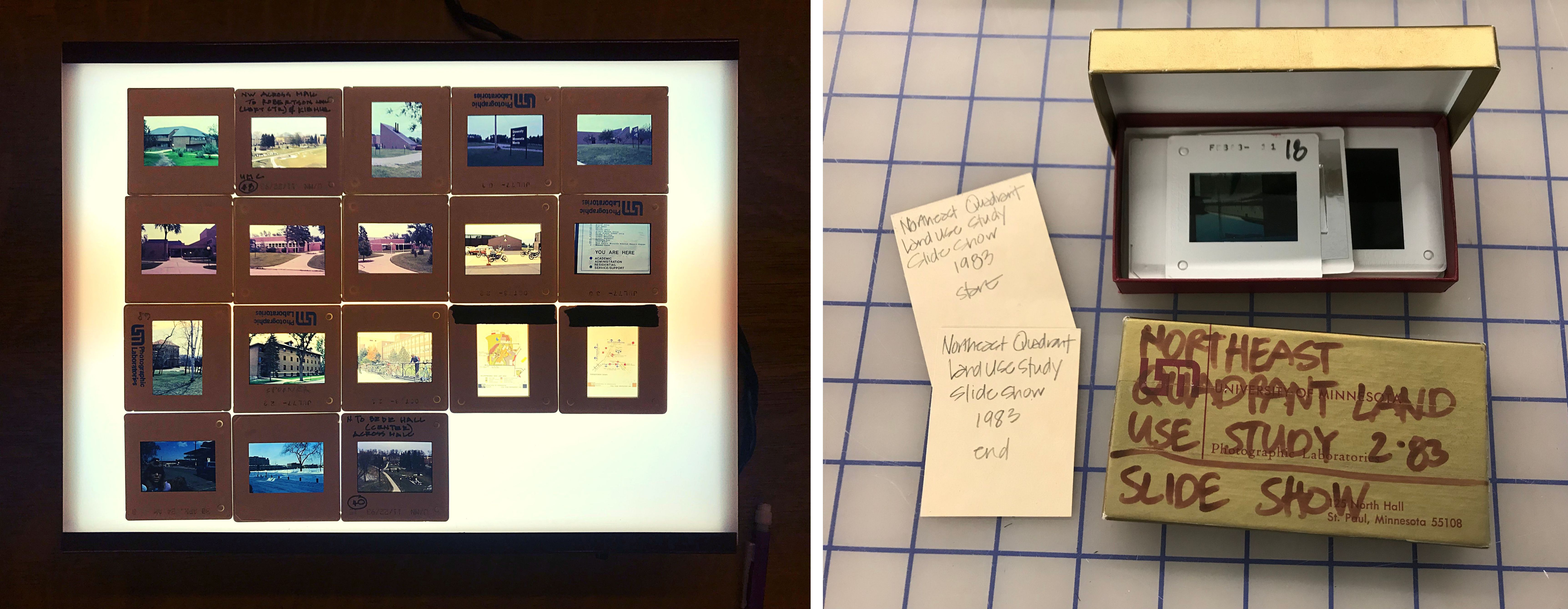

Smoot met Hewitt when he began teaching in the department and the two became fast friends. When Hewitt phased into retirement, it was Smoot who spent long afternoons helping him sort through his office, often getting sidetracked by memories from Hewitt’s accomplishments. Faced with his life’s work packed in boxes, Smoot connected with Archivist Rebecca Toov to carefully organize and digitize artifacts of Hewitt’s career.

When asked to name her favorite piece from the archive, Toov recalled the guidebook, Signage and Graphics Standardization Program for the University of Minnesota (1977), which outlines the size, placement, typeface, and position of the lettering on signs throughout campus—a distinct feature of the University of Minnesota aesthetic. “I now think of Clint Hewitt whenever I spot those lowercase Helvetica letters on campus,” Toov said.

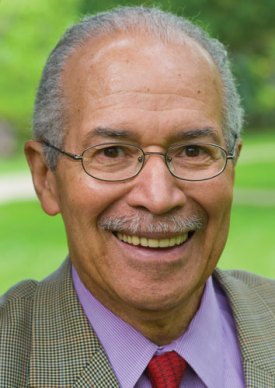

Stacks of colorful boxes filled with documents and slides from the Clint Hewitt archive. Credit: UMN Archives.

Hewitt took every aspect of his work, from lettering decisions to major construction, and brought it close to his heart. No matter the scale of his undertaking, projects in Hewitt’s eyes were always defined by relationships and shared values.

“Clint understood the undocumented nuances involved in moving a project through the campus planning process. Some might call that politics or red tape, but Clint understood it as a series of relationships. He also brought a personal lens to this work, by relaying his experiences,” explained Landscape Architecture Department Head Joe Favour. “His stories conveyed how his upbringing played a role in his values and how those values and education were expressed in the work he helped to create. In this way, he revealed the more complex role of a designer by helping others see how much of the work is about process, discussions, and project management.”

Slides and hand-written notes from the Clint Hewitt archive. Credit: UMN Archives.

Hewitt taught from experience, drawing from decades of professional practice to illuminate abstract topics to students. This narrative style embellished with real-world examples epitomized his teaching and mentorship of others. “I still think of his stories and his calm presence in studio,” reminisced Noah Billig (MLA + Masters in Urban Design & Planning, ’07). “I most fondly remember visiting his office—he had a great knack for creating space and time for students.”

The graduate design studio course Billig recalls so warmly was the pilot of what is now a 17-year-long collaboration with Juxtaposition Arts (JXTA). Originally co-taught by Hewitt and Professor Kristine Miller (Landscape Architecture), UMN design students worked with JXTA’s environmental design students to develop ideas for the main commercial corridor in north Minneapolis, West Broadway, which was slated for redevelopment.

“That first semester was so successful that JXTA was hired to work on the city’s West Broadway Alive! Plan to creatively connect with people to bring more voices to the planning process. Clint introduced students to concepts of strategic planning like SWOT analyses and worked with students one-on-one to understand what inspired them. As a result, their work was grounded in reality and also shaped by who they were as designers and humans,” said Miller.

Yet what then-graduate student Danyelle Pierquet (MLA, ’06) remembers most keenly is the atmosphere Hewitt created. “My treasured memory from that studio is turning the lights low, turning on the image projector and some jazz, and sketching for a few minutes. It was a great reminder to take a beat and recenter,” described Pierquet.

Cover and quote from a collection of jazz musicians curated by Clint Hewitt. Credit: UMN Archives.

The archive captures these intangibles along with the several decades-worth of concrete materials that tell the story of Hewitt’s career and a significant piece of UMN’s history. “His body of work helps us understand the timescale of landscape architecture and campus design, which is measured not in years but in decades or centuries,” observed Favour.

His paper trail details how to hold a vision over time; how to communicate that vision across projects, relationships, administrations, and contractors; and how to respond to and anticipate change both in terms of systems and landscapes.

“Within landscape architecture and architectural history, the collection is also critical to our understanding of the important role of Black designers and planners,” remarked Miller. “To me, everything he has accomplished is even more inspiring when considered alongside the obstacles he overcame. I believe that Clint will take his place within the history of campus design and planning overall and his place among Black landscape designers, architects, and planners like Julian Abele and David Augustus Williston.”

The buildings, interconnected spaces, and infrastructure that Hewitt shaped at the University of Minnesota campuses will last generations, and now, thanks to the archive, Hewitt’s vision and perseverance which brought those projects to life, will be preserved.

Early interaction with nature has been proven to increase children's capacity for creativity, critical concentration skills, and relationship building.

Longtime professor, mentor, and leader in the Twin Cities design community Joe Favour (B.L.A. ’92) began his appointment as head of the Department of Landscape Architecture this June.

On May 6 and 7, 2021, the Department of Landscape Architecture will host capstone presentations for the Master of Landscape Architecture Class of 2021. Members of the public are invited to watch the presentations. View the presentation schedule and learn about the capstones that will be presented below.