In 1980, Lee Anderson (Architecture) was deep into his M.Arch thesis on fractals and design when he realized that in in order to generate graphics to represent his ideas, he’d need to learn computer programming.

Anderson taught himself as much as he could, then reached out University of Minnesota experts in computer science, fine arts, and IT. His resulting thesis was the first presented using video, which caught the eye of Ralph Rapson, who recognized that computer graphics would become more and more important for architects.

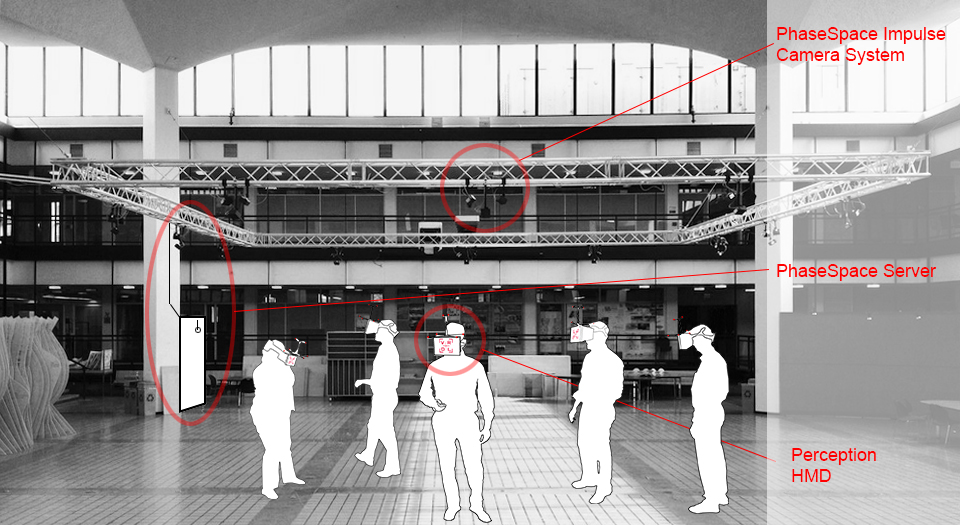

Rapson asked if he’d like to start teaching, and since 1981, Anderson has taught generations of students in the School of Architecture how to use cutting-edge technology to refine and represent their designs, served as interim department head and associate dean for research, and led the development of our world-class Virtual Reality Design Lab.

In honor of his upcoming retirement, we asked Anderson what’s next for virtual reality (VR) and how it could transform design as we know it.

Could you talk us through the representation technologies that the School of Architecture has transitioned through during your tenure here?

So many that it’s difficult to describe!

Initially, CAD. 2D drawing software was just coming in when I was hired in 1981. And at that time, we saw the beginning of the switch from mainframes to PCs, and very soon after the Macintosh. In the 90’s, being able to draw directly in 3D was something of a revolution. In the last five to 10 years, building information into modeling has had a big influence; it really caught on with Revit and MicroStation.

And now, virtual reality. It’s been around for a long time, but the hardware to be able to really do it has exploded in about the last three years. Today we’re at the cusp of making this hardware available at a reasonable price to just about anyone who wants to use it. This year is the edge.

So how do you think VR will transform the way architects work?

In my personal opinion, the emphasis on computer graphics such as SketchUp and Rhino has emphasized the exterior of a building. When you have a building sitting as a chunk on your screen, you understand it as a piece. That creates a tendency to think of a building as an object and design it as an object, and so form becomes the overarching consideration. And because we see form as surface, surface treatments become very prominent.

Now, virtual reality will still allow you to view the building as a model. But you can also put yourself inside of it one to one, and then your design considerations shift to: what do I see? Where am I? What kind of space am I designing? You’re thinking more about the space that you’re occupying, rather than an image of a chunk on the screen.

Orbit and zoom are very stiff, formal ways of changing a view. We have a much better understanding of things when we’re using our body to move our eyes. And virtual reality, you might say, reunites our eyes with our bodies in the way that we’re used to using them.

I have had students who go into their model in VR and for the first few seconds, they think they’re in someone else’s model. The model feels so much different than they thought, and once they get inside of it, they don’t understand it anymore. That gives you an idea of how differently virtual reality can present a design: they don’t even recognize a model that they’ve built every bit of.

Can other designers use VR?

Absolutely! Retail merchandising professionals build virtual store displays, so VR can demonstrate what is it like to walk through it. Interior design, graphic design, and other careers as well. For example, city planners need to represent new buildings to citizens groups who are interested in how a project will affect their neighborhood. VR is by far the best way to do that: if you put them right there, they move around and experience the scale and feel of things.

How do you think VR technology will change the relationships between designers and their clients?

Visualization is always important in architecture. Unlike a sculptor or a weaver, we don’t actually make the thing. We have to represent it completely—to ourselves, to our clients, to the people who are going to build it. And so any change to our ability to represent buildings means there is a potential for a great change in architecture.

Virtual reality reintroduces the personal viewpoint that has been denied to non-designers by traditional drawing methods. Everyone looks at things differently, depending on their backgrounds, what they’ve seen before, how they understand things. VR allows that to happen, as opposed to just showing them a rendering of the new office from a particular viewpoint. Rather than just giving feedback on that specific perspective, they have the opportunity to dig a little deeper into the elements that are relevant to how they’ll experience the space. In past uses, we’ve had clients of our professional partners change their mind about what they want based on what they see in VR.

Just about anyone who designs something is going to want to be in VR very soon. I think probably within a couple or three years, pretty much every architecture school and firm will have some kind of VR capability.

Congrats again on your retirement! What’s next for you?

Aaron Westre, Phil Rader, and I in the Virtual Reality Design Lab have been working with the venture center in the Office for Technology Commercialization. We have formed a little company called R5VR to commercialize the virtual reality tech that we’ve developed at the College of Design.

Our software can take models that have been built in SketchUp and rendered in LightUp, then export a file that you can immediately show it in Oculus Rift or the HTC Vive or Google Cardboard. It’s the only software of its type, and we’ll be starting to sell it later this summer.

The College of Design is excited to welcome a number of new, full-time faculty and staff to the college this fall. In addition, a number of our current staff and faculty have moved into different positions within the college.

An interdisciplinary partnership between College of Design faculty, the Goldstein Museum of Design (GMD), and Episcopal Homes Senior Housing and Care Services is developing virtual reality (VR) technology to expand access to exhibitions and other public events for low-income elder residents through the creation of a “VR Book Club.”

On June 8, 2020, the College of Design named Jennifer Yoos, FAIA, as the new head of the School of Architecture. Her career in architecture is driven by a lifelong love for art, buildings, and design in general as well as childhood summers spent with her artist aunt in Chicago. In our interview, Yoos shares her visions for the school, the new semester, and the future of the profession.