With the highest maternal mortality ratio in the world, Sierra Leone is one of the most dangerous countries for women to give birth.¹ Architecture graduate student Gauri Kelkar’s final project is helping to change that.

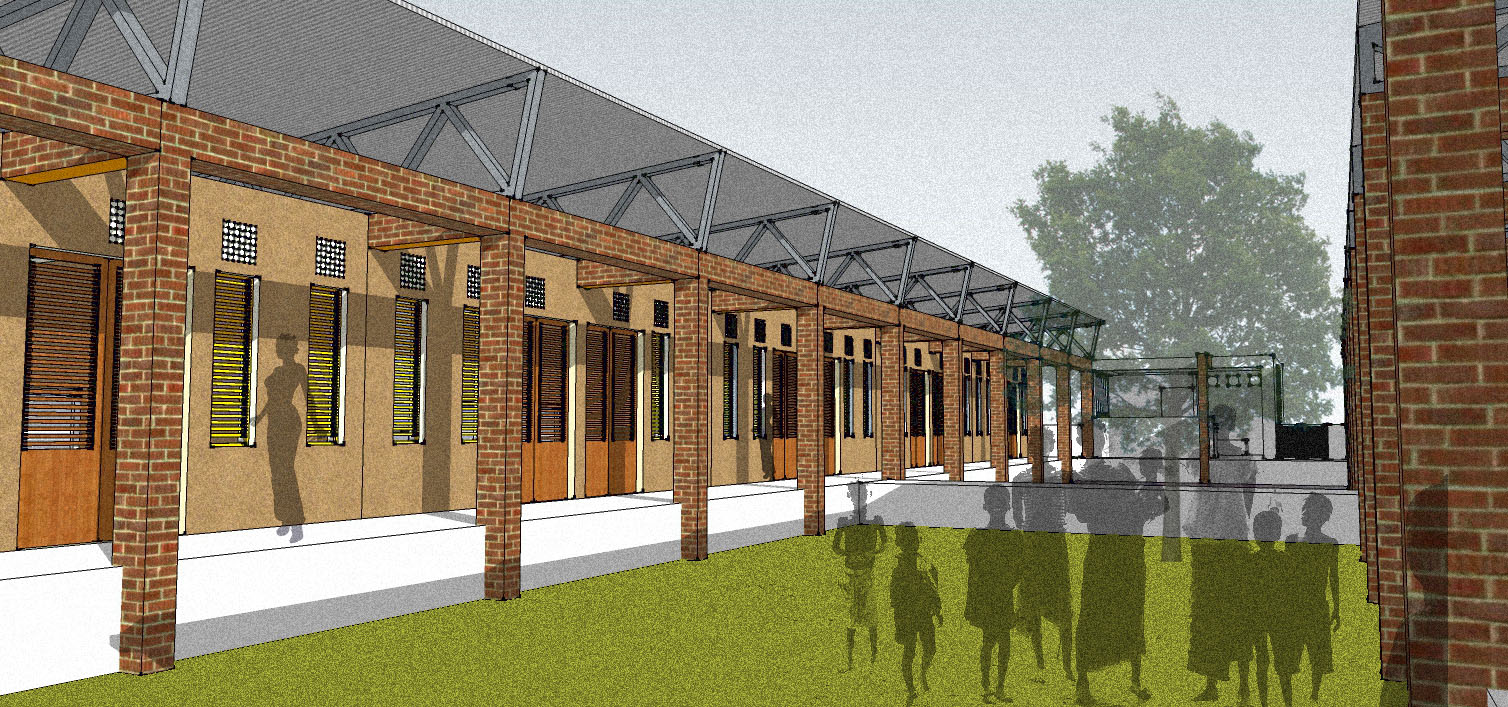

Partnering with Rural Health Care Initiative (RHCI), a Minneapolis-based non-profit founded by Sierra Leone immigrant Alice Karpeh, Kelkar designed a birth waiting house (BWH) in the Sierra Leone village of Tikonko. Once completed, the BWH will provide a location for women to receive pre- and post-natal care, education, and assistance if complications arise.

In this interview, Kelkar shares more information on the project and the steps that have gone into its construction thus far.

How did you create the plan for the birth waiting house?

One of the first tasks was gathering data about the context and developing an understanding of both Sierra Leone and Tikonko — its people, their lifestyle, culture, building traditions, and climate. The focus of this data gathering stage was three-fold:

- Study the cultural, social, and climatic aspects of Tikonko and the site.

- Study the building traditions and construction typologies.

- Study of maternity birth waiting homes to help define a program for the center.

Since travel to Sierra Leone was not possible for me, I spent a lot of time doing archival research, having conversational interviews with RHCI members and volunteers, and examining case studies of similar projects in Africa to try to develop an understanding of the region.

The design of the building itself was a collaborative process with periodic input from RHCI members and the local Sierra Leonian community in Minneapolis. These conversations served as a ‘reality check’ for my design process. Their questions helped the project stay rooted in its surroundings and kept me sensitive to their needs.

What considerations did you take into account while you developed the building plan?

The idea is to have this building be self-sustainable and culturally appropriate to function as a resource for the whole community of Tikonko. The site has no running water, electricity, or sewer connection, so it was essential to quantify what was naturally and freely available. We had to be able to leverage resources like sunlight, wind, and rainwater effectively. The building plan had to give a sense of openness and yet provide privacy to pregnant women who were living at the center. The orientation and location of the building on the site, the placement of different functions, and the massing of the building were all influenced by questions like:

- What climatic aspects need to be taken into account?

- How to reduce standing water, mosquitoes, and resulting Malaria?

- What services does RHCI plan to provide at the BWH?

- What is the lifestyle of the local Sierra Leonian people?

- Will they feel comfortable and safe in the building?

What was the most challenging aspect of this project?

The most challenging part was designing for a community and culture that I was unfamiliar with. The project client was RHCI but in reality, my user group for the building was the pregnant women of Tikonko and surrounding villages. Channeling their needs was tough. I had to rely on what I gleaned from other people’s experiences of Sierra Leonian culture and traditions. Designing without visiting the site and relying on photographs was equally challenging.

What was the most surprising thing you learned during the course of this project?

As part of my research to understand what it means to be pregnant in rural Sierra Leone, I read a book called Monique and the Mango Rains. The author, a Peace Corps worker, spent two years shadowing a midwife in West Africa.

The book was an eye-opener for me. I was shocked by the conditions in which women give birth and the distances they have to travel to give birth. Some of the complications faced by these women are exacerbated by the lack of access to prenatal care, proper nutrition, and medical professionals. These are things many of us take for granted and the conditions these women face exemplify the need for community clinics and the BWH.

How close to completion is the birth waiting house?

Construction continues on the BWH with exterior walls, roof, windows and doors of the main building and restroom block complete. Finishing the interior of the buildings is next and then the triage building, which is required by the Ministry of Health & Sanitation, will be built. Everyone in the village, especially the midwives and women of the village, is excited about the building and what it brings to the community.

Help RHCI complete the construction of the birth waiting house by donating here.

¹Mason, Harriet. “Making Strides to Improve Maternal Health in Sierra Leone.” UNICEF. UNICEF, 26 May 2016. Web <https://www.unicef.org/childsurvival/sierraleone_91206.html>.

For architecture students, the road to becoming licensed is a long one. Between school, internships, and preparing for the licensure exam, the mean time from high school graduation to becoming licensed is 13.3 years.¹

The self-checkout counter. It’s a common sight in grocery stores across the nation. But what impact does it have on the design of a store and on the people who use it?

Architecture students in Professor Julia Robinson’s (Architecture) Studio V are preparing design proposals to reconsider how to serve youth presently in Hennepin County’s juvenile detention and rehabilitation centers.